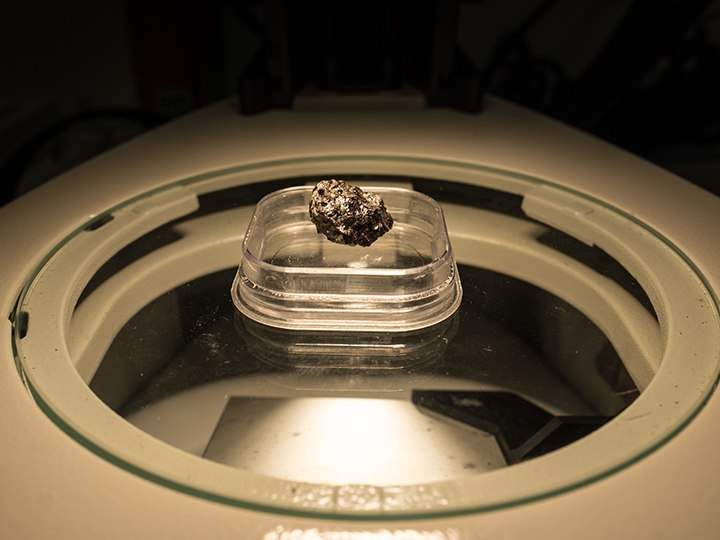

In July 2011, a meteorite from a Martian volcano fell in the Moroccan desert, and fragments of it rained across a wide area. Several people saw this happen— which is rare— and quickly grabbed what they could. Since then, scientists from around the world have been studying pieces of the Tissint meteorite, named after the small town in Morocco where it fell. They’re looking for evidence of life on the red planet.

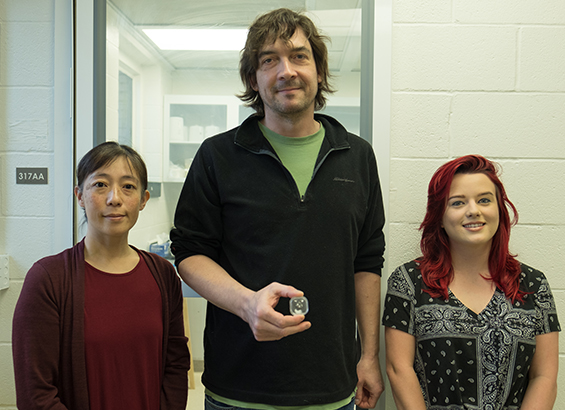

At the University of Houston, a team of researchers in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics is analyzing a few small fragments with the help of a $349,520, three-year grant from the NASA Solar System Workings program. The research team— geology professor Tom Lapen, researcher and lab supervisor Minako Righter, and geology graduate student Stephanie Suarez— is trying to answer an important question: Just how old is this rock?

Preliminary analyses of samples of Tissint fragments have revealed conflicting ages. Lapen and his team think it’s possible the fragments may include material from multiple rock layers that formed at different times on Mars.

“The crystallization ages would be the time at which the lava flowed out as magma and then crystallized,” he said. “So the observations are that in this one witnessed fall, there is evidence of multiple flows.”

In addition to Tissint, the research grant will facilitate analyses of other Martian meteorites from Northwest Africa and Antarctica with the goal of learning more about the volcanic history of Mars and the evolution of the Martian lithosphere, which includes its crust and upper mantle.

“The only samples we have to study directly are meteorites. These rocks are probes into the deeper portion of the planet, and from that, we can say something about the interior of the planet,” Lapen added. “We can’t actually sample the interior, but we can look at what comes out.”

The University of Washington and University of Wisconsin are collaborating with UH on this project.